PNGAA Library

The Kula Ring: Chips Mackellar

A story of survival in the Solomon Sea

When the search for the missing MH370 Malaysian Airways jet is finally over, it will be an amazing story to tell. But there is another amazing story of loss at sea, not as spectacular as that of MS370 but with a happy ending.

I was Assistant District Commissioner, Trobriand Islands, when one day a blind man on Alcester Island lay down on a beached canoe in the warmth of the afternoon sun and dozed off to sleep.

No one on the island took any notice of him as they were used to seeing him asleep on beached canoes. But later, when his family went to fetch him for dinner, they found the canoe had gone.

By then it was dark and the canoe was nowhere in sight. The tide had come in, lifted the canoe and it just floated away with the blind man still asleep on board.

The alarm was raised and people ran up and down the beach calling frantically to the blind man, but there was no response.

In desperation, they took to the sea in other canoes, and paddled around the island in the dark but still did not find the missing blind man or the canoe.

The search went on all night until the first light of dawn, when it was obvious that the sea was empty in all directions. The canoe had disappeared.

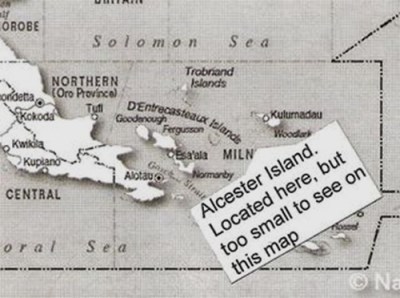

Reluctantly, the search for the blind man was abandoned because there was nothing else the islanders could do. Although Alcester is an idyllic island in all other respects, it is a speck in the ocean, miles from anywhere.

There was no radio on the island, no power boat, the only communication with the outside world was by their own canoes or visiting canoes from other islands or passing coastal vessels bound elsewhere.

Fortunately one such vessel called in at the island a few days after the blind man went missing. It had a radio aboard and contacted with District Headquarters at Samarai, raising the alarm and beginning an air-sea rescue operation.

Scheduled flights to the Trobriands were diverted south. Flights to Misima were diverted north. Chartered aircraft out of Alotau searched north-east. And coastal vessels plying the Solomon Sea were asked to keep watch.

The Trobriands were considered too far north of Alcester Island to be useful in the search so we were not called on to assist. However, we followed the progress of the search by listening to radio reports which came in from time to time.

But the blind man and the canoe were not found, so after two weeks of disappointment the search was called off and he was officially declared probably lost at sea.

This is not the end of this story. About a month after the search had been called off, villagers from the southern end of the main Trobriand island of Kiriwina brought the blind man to the Sub-District Office at Losuia. He was seeking assistance to return to Alcester Island.

I could hardly believe it. Not only was he alive. He was very well. I sent him to the doctor, just to make sure. The doctor said the blind man was fit to return to Alcester Island and had suffered no ill effects from his ordeal.

And what an ordeal it must have been. Yet when I told him about the air-sea rescue which had been mounted to find him, the blind man couldn’t understand what all the fuss had been about.

The blind man explained that, when he woke up on the canoe, he knew it was dark because he could no longer feel the warmth of the sun on his skin. He also knew the canoe was floating in the sea because he could smell the water and feel the canoe rocking when he moved, a situation confirmed when he put his hand in the water.

He called for help to get back to the island, but received no reply. He assumed that people on the island would also be calling out for him but he could not hear them, so he knew the island was out of earshot.

He felt around the canoe and found a paddle. He could have paddled back to the island if he had known where it was. One problem was that the sea was big and the island was small and, even if it had been visible, he could not see it. So he did not know in which direction to paddle.

He also knew that if he paddled in the wrong direction, he might never make landfall alive. Adrift and alone in an empty sea might have been bad enough for ordinary people, but for a blind man alone in a canoe, it was infinitely worse.

“So what did you do?” I asked him in Motu.

“Well, Taubada,” he replied, “since I did not know where Alcester Island was, there was no point in attempting to return there.

“I knew that Woodlark Island was directly north of Alcester, and it was a larger island and therefore more easy to find, so I decided to head for there, until I could beach the canoe either on Woodlark Island, or here in the Trobriands.”

“These island are miles apart,” I said.

“Yes,” he replied, “but even if I could see, there was no way I could compensate for drift and current, so by heading north the chances were that if I missed Woodlark, I might still land in the Trobriands.” I was astonished at his good, sound reasoning.

“Have you been here before?” I asked.

“No, Taubada,” he said, “I had been to Woodlark before with other people in another canoe. But I have never been here before.”

I was amazed. “So how did you know where the Trobriands were?” I asked. “From stories people told,” he said, “you know Taubada, the Kula.”

Ah, yes, the Kula Ring. The customary system of ceremonial exchange which formed the traditional social bond between people of different islands.

We had several anthropological publications about it in the office at Losuia. Malinowsky, Fortune, Uberoi and the rest. I had read them all. They explained that from the Trobriands in the north to Wari Island in the south, from Milne Bay in the west to the Laughlan Islands in the east, the people of 18 different island groups across the Solomon Sea were connected by this invisible ring of ceremonial exchange.

Invisible to us, that is, but to them it was a social bond more real than the strongest kinship ties. No one knows how it all began and it is overlaid with myths and legends and magical rites and rituals. But it has a powerful practical purpose.

The Kula Ring involves strong mutual obligations to provide hospitality, protection and assistance to partners of the same Kula artefacts. Thus, any Kula associate from any one island in the Kula Ring, blown off course, marooned, washed overboard, or in any other way distressed from the sea, must be provided with sanctuary, protection and assistance from any other Kula partner on any other island in the Kula Ring.

Even if they have never met before, the bond between them has already been established by the ceremonial exchange of Kula artefacts passed on from one man to another from other partners on other islands elsewhere in the Kula Ring.

In other words, the Kula establishes an invisible bond of indissoluble brotherhood which is spread unseen across reefs and islands and coral atolls to the far reaches of the Solomon Sea.

So, unable to find Alcester Island, and confident that he might find safe haven somewhere else in the Solomon Sea, the blind man paddled his canoe in the direction of Woodlark Island.

“But how could you navigate your canoe,” I asked, “if you could not see where you were going?”

“I could not see,” he said, “but I could feel the sun’s heat.” And he went on to explain that if he kept the sun on his right side in the morning, and on his left side in the afternoon, he would roughly be heading north. So by paddling his canoe in this way he headed for Woodlark Island.

“You could not see the stars,” I said, “so how did you navigate at night?”

The wind was blowing from the south-east, he told me, so he knew he was travelling northward because of the sun’s heat during the day, and when heading this way he could feel the wind on his back.

So, he said, when the sun had set he paddled with the wind on his back until morning, then, with the sun rising on his right side again and the wind still at his back, he knew he was more or less, on course during the night.

And so, long after the official air-sea rescue had ended, the blind man’s own search for a safe haven continued.

“But you were paddling your canoe for weeks,” I said, “What did you eat and drink?”

He said he felt around inside the canoe and found a bailer shell. Sometimes it rained, he said, and the rainwater would collect inside the hull of the canoe. Instead of bailing it out, he left the rainwater to slosh around inside the hull and he used the bailer shell to scoop it up and drink it.

“And food?” I asked. There were flying fish, he said. They skipped across the sea and over his canoe, but some did not make it across and fell into the hull whence they could not escape.

He said he could hear them jumping around inside the rainwater in the hull and after a while they died. He said he could not see them, but by feeling around inside the rainwater, he could catch them and eat them raw. There weren’t many, he told me, just a few every day, but enough to keep him going.

“And landfall?” I asked, “Tell me about that.” After a few weeks of paddling in the direction of what he thought was north, he told me he could hear the surf breaking on a shore somewhere.

He did not know where, but he could hear sea birds flying overhead and he could smell land: palm trees, smoke from cooking fires, the smell of a village. So when he knew he was close to shore because of the back swell from the beach, he began to call out the name of his Kula artefact.

He called and called and called, he said, and soon he could hear voices from the village and some shouting. Then amongst the shouts he could hear the name of his Kula artefact being repeated by one of the village men who identified himself as the local Kula partner of that artefact. The blind man then knew that his search for a safe haven was over.

People swam out through the surf and guided his canoe to the beach, and that is how he made landfall. “I missed Woodlark Island,” he said, “but I found the Trobriands instead.”

His Kula partner, whom he had never met, fed him and cared for him in the village until he was fit enough to continue his journey, and then the village people brought him to my office.

As soon as I received the doctor’s report, I sent a signal to District Headquarters in Samarai and everyone there was just as amazed as I was that the blind man had made it safely to the Trobriands.

I was told to put him on the scheduled air charter from Alotau the following day, and from Alotau I heard that he went by shuttle vessel to Samarai and from there by government trawler back to Alcester Island.

From Alcester Island to the Trobriands, the blind man had paddled and drifted for approximately 320 km. In an open canoe travelling solo, it would have been a remarkable feat of survival for anyone, for the blind man travelling alone it was almost a miracle.

Yet when I discussed the blind man’s miraculous survival with the Paramount Chief of the Trobriand Islands, he was signally unimpressed. “We have been sailing across the Kula Ring for a thousand years,” he said. “Canoes get lost, blown off course, break up in rough seas, or get swept on to coral reefs and atolls.

“It doesn’t happen very often, but when it does happen we know what to do. Your search with ships and planes could not find this blind man,” the Paramount Chief continued, “but he knew what to do, and it was his own search for a safe landing which saved him.”

“But he was blind,” I insisted.

“Yes,” the Paramount Chief continued, “but he still knew what to do, and that is the way it is in these islands.”

I was astonished that the Paramount Chief was so unimpressed by the blind man’s ordeal.

“It was nothing special,” the Chief continued, “it was just another event of life in the Kula Ring.”

It might have been, but I will always remember the amazing feat of endurance, determination and skill of a blind man paddling a canoe solo for 300 km in search of a safe landing, out there in the solitude of the Solomon Sea.