PNGAA Library

An ounce of gold and a model aeroplane: Michael Waterhouse

Three intriguing artefacts tell the story of New Guinea gold-mining pioneer Cecil Levien.

In September 1954, three unusual items were left to the Mitchell Library in the will of a Mrs MM Levien: the first miner’s right issued in New Guinea (to her husband Cecil Levien), the first ounce of gold obtained from the Bulolo mine, and a model aeroplane presented to Levien in 1927. No explanation was provided for the bequest, nor any information about its significance.

The extraordinary story that links these three items was the inspiration for Ion Idriess’ highly popular 1933 novel Gold Dust and Ashes. Historical accuracy was not his great strength, but Idriess was a superb communicator and the book went through 26 editions over the following 30 years.

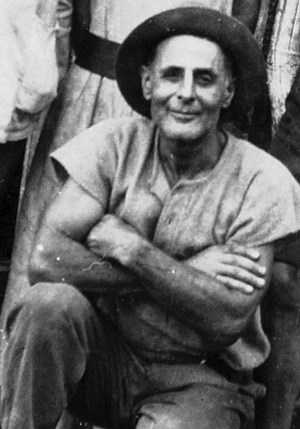

Following years as a largely unsuccessful gold miner and farmer in Australia, and a stint training at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, Cecil Levien joined the military administration in New Guinea in 1919, transferring to the new Australian civilian administration in 1921. He was tough, wiry and resourceful and in July 1922 was appointed Acting District Officer, Morobe.

Some distance inland, though the area was still closed to mining, Shark-Eye Park and his mate Jack Nettleton were illegally extracting gold from Koranga Creek, a small tributary of the Bulolo River, using crudely fashioned sluice boxes. And they were doing well. But after they experienced trouble from marauding Kukukuku villagers, a patrol officer went in to settle things down. In their camp, he saw six bags of gold that Park and Nettleton had already accumulated and reported this to Levien.

In mid-December 1922, Levien visited Koranga Creek. What he saw made him realise his future didn’t lie with the Territory’s administration. A fortnight later, the new mining warden, Jack Lukin, issued the first miner’s right to Levien. While it gave him the right to apply for a claim, Lukin’s annotation suggests he thought Levien had taken it up merely as a curiosity.

Levien certainly intended to resign from the Administration and become a miner, but he also had a bigger scheme in mind: to peg leases on and around the Bulolo River and on-sell these to a syndicate in which he would retain a share.

Mining became legal on 1 April 1923, and a fortnight later applications were made for four leases, Kaili 1, 2, 3 and 4. The applicants were all apparently dummies for Levien himself. The leases were pegged by Shark-Eye Park, for whom Levien had been quietly providing supplies since his visit four months earlier. Over the next few months, using a mining engineer as an intermediary, Levien offered a group of potential investors an option over the leases, and in August 1923 Kaili Gold Options NL was formed.

Under the terms of the deal, Levien was to contribute £1000 towards the cost of testing the leases. If the results were good and the option was exercised Levien would receive £10,000 cash and 25% of a new company to work the leases. However, events were conspiring to force Levien’s hand. His efforts to discourage another experienced prospector from reaching the Bulolo aroused Lukin’s suspicion, who reported his concerns to the Administrator. In September, the Administrator asked Levien to respond to Lukin’s allegations. Unconvinced by Levien’s account, the Administrator asked him to resign.

Within days, Levien was on a ship to Melbourne, carrying 250 ounces of gold from Koranga Creek. In an effort to generate enthusiasm among investors, the gold was put on public display in October 1923 at the offices of the Secretary of Kaili Gold Options. The small sample of gold bequeathed to the Mitchell Library is believed to be from that display, probably retained by Levien for sentimental reasons.

The next 18 months proved the old adage ‘When one door closes, another opens’. Testing demonstrated that large-scale mining of the Kaili leases was unlikely to be economic and the option was allowed to lapse. Downstream from the leases, however, the Bulolo River opened out into a broad valley. Levien had come to the view that, over the ages, gold would have been carried downstream and distributed across the valley as the river slowed. He envisaged a major dredging operation powered by hydro-electricity, with planes flying in all the machinery required from the coast over otherwise impassable country.

Australian investors showed little interest in Levien’s vision until early in 1926 when news reached Australia of a rich gold discovery at upper Edie Creek, a tributary upstream from the Bulolo valley. Levien adroitly used the discovery to promote his scheme, and gained sufficient interest from investors to form Guinea Gold NL, in which he had a 25% interest.

As the company’s field superintendent, Levien pegged six leases covering 1050 acres (425 hectares) in the Bulolo valley. Labourers carved an aerodrome out of the jungle on the Lae waterfront and constructed another on a steep gradient at Wau. Under pressure from Levien, Guinea Gold acquired a De Havilland 37 biplane, which arrived at Lae in March 1927: the first aeroplane to fly in New Guinea.

While Levien’s obsession with air transport was driven by his vision for the leases in the Bulolo valley, he soon realised it was highly profitable in its own right. He exerted pressure on the Guinea Gold Board to establish a new company, Guinea Airways, and acquire a Junkers W34, with a payload of 2000 lbs (900 kg), three times that of the DH37. The model held by the Library commemorates Levien’s role in purchasing the first of six W34s acquired by Guinea Airways.

Meanwhile, Guinea Gold was fast running out of money. In April 1928 it was saved from collapse when a small Canadian-based mining company, Placer Development, purchased an option over the Bulolo leases. Within 12 months, testing revealed values similar to Levien’s earlier estimates, justifying the construction of two dredges and a hydro-electric power plant. But it would be several more months before the final piece of Levien’s vision fell in to place, with a decision to acquire two of the world’s largest planes—Junkers G31s—to fly dredge parts from Lae to Bulolo. A seminal event in the country’s history, the launch of the first dredge in March 1932 attracted Europeans from all over the Territory.

One person was missing, however. Cecil Levien had died suddenly of meningitis two months earlier while on a visit to Melbourne. Two days later, his ashes were taken up in one of the G31s and scattered over the Bulolo valley: his were the ashes in the title of Ion Idriess’ book.

The years that followed proved the validity of Levien’s vision in a spectacular way. Placer Development’s operating company Bulolo Gold Dredging constructed eight dredges, flying in everything required on the two G31s. Up to the Japanese invasion in January 1942, the dredges produced 1.3 million ounces (36,850 kg) of gold and 600,000 ounces (17,000 kg) of silver.

Throughout the 1930s, New Guinea led the world in commercial aviation. Its planes flew more than half as much freight as those in the US, Canada, Germany, France and the UK combined. In no year did any other country’s planes carry more.

The three items bequeathed to the Mitchell Library are all ‘firsts’. Levien was a proud man and doubtless regarded them as historically important. It’s likely that, before his sudden death, he talked to his wife about their significance and that her donation was, in effect, carrying out his intentions. Whatever the reason, they remain symbols of a remarkable man, whose vision and persistence transformed New Guinea between the wars.

First published in SL Magazine, the magazine for Friends of the State Library of NSW, November 2015.

Historian Michael Waterhouse is the author of Not a Poor Man’s Field: The New Guinea Goldfields to 1942 — An Australian Colonial History (Halstead Press, 2010).

Levien’s gold and model aeroplane are on display in the Amaze Gallery.

Cecil Levien. Photo: Michael Waterhouse

First ounce of gold from the Bulolo mine, c.1923

Model given to Cecil Levien of the first Junkers W34 acquired by Guinea Airways, LR 42