PNGAA Library

Bad day at Slate Creek: Ralph Sawyer

Hector and Baden Wales belong to that select band of prospectors who opened up the goldfields in the 1930s. The brothers worked at Edie Creek, Watut River and the Bulolo River. They were pioneers in the use of high pressure hoses to bring down the alluvial banks along the streams. They also diverted streams so that they could get at sand and gravel in deep sections of the river.

Hector reputedly held the record of 1000 ounces of gold in a calendar month. It’s a pity the going price was only two pounds ten shillings an ounce. Ever the prospector, Baden was still prospecting for gold on the upper Lakekamu River 30 years later. At periodic intervals he would retreat to Kukipi and Kerema (DHQ). Here he would recuperate from his emaciated state with the Murphys and the Ryans.

Frank Ryan DAO would employ Baden as a casual to build copra smoke houses for local village cooperatives. The author met Baden while he was on one of these tasks at the station. The writer hopes that the subsequent story does not diverge too greatly from the facts and times but 1933 is 83 years ago and there is no one left to confirm the details (or deny them!).

I thought I was happy selling tickets at Roma Street Station. That was before my cousin Hector tapped on my glass window.

‘Hector Wales - your aunty Edna's boy - down from New Guinea - like to say g’day - see you after work - Canberra hotel, Anne Street.’

Hector always spoke in telegrams. Saved time. I found my two cousins Hector and Baden in the front lounge, two gaunt young men, old for their age. They looked ill at ease in this Edwardian tearoom. The Canberra was a Temperance Hotel where dainty waitresses in black and white uniforms bustled about serving tea and buns.

We repaired upstairs to their room where we exchanged formalities and familiarities with Bundaberg Rum Negrita. Now I felt uncomfortable, especially with that large sign on the door:

Alcohol is strictly forbidden on the premises.

Entertainment of female visitors after 6pm is prohibited.

The wild thought flashed through my mind. I wonder if anything goes on earlier in the afternoon. Probably not. Hector got to the point. On Leave – prospectors - done good at Edie Creek - need a man - going back soon. Baden chimed in by producing three woollen socks full of gold dust.

‘Our takings from Edie Creek. Not bad eh.’

Hector almost waxed lyrical but soon slipped back into his staccato style.

'Don’t trust banks - been assayed 2-15-0 an ounce.’

Between Hector and Baden, who almost spoke English, they laid out the deal. They were going back to the upper Watut River to try a new area even more remote than Edie Creek. They needed a reliable man to shuttle gold, rations and labourers to their working claim. The deal was 33 percent of net takings. Hector finished the proposition off with the sting.

‘Remember - don't strike it – 33 per cent of bugger all.’

The vision of New Guinea, palm trees, natives, sea voyages and gold was too much for me. I chucked in my job and hung my star on the Wales brothers. The next month was a blur of hotels, race meetings and pictures. King Kong was one of them and King Richard was another. One of them was a horse. Baden bought a new Ford roadster which he promptly crashed into a tram in Queen Street.

‘Bit rusty, let’s go.’ was Hector’s response.

We left the crowd arguing and went back to the car dealer in Leichardt Street. Baden paid another £32O and off we went again. The gold dust ran out and the Commonwealth Bank stopped smiling so we shipped out on a Burns Philp fuel ship from Hamilton Reach. Baden actually left the car on the wharf!

I carried an entry permit to New Guinea which cost £100.

The surety guaranteed to return passage to Brisbane should George Wilson become a vagrant with no visible means of support. The surety also covers the cost of burial should the permit holder die a pauper whilst a resident of the Territory of New Guinea.

Fully guaranteed and insured I reached Salamaua, the entry port for the gold fields. There was no customs official to stamp my papers. The drums of benzine were dumped overboard and floated into the beach. The heavy cargo was ferried ashore on a platform on top of three canoes. The passengers got ashore as best they could.

Baden and Hector immediately subcontracted 25 carriers and labourers from Sid Campbell, a registered recruiter. Terms were £1 per month, rations, wet weather gear and return fare to their home district. In return the workers were bound for two years with penalties for desertion. Baden set out up the track with his labour line while Hector and I organised another 25 Sepiks to carry more rations, tools and camping gear.

Ten days later we set off on an eight day trek up into the mountains. Nothing prepared me for the ordeal ahead. Heart breaking climbs, desperate descents, scorching days, torrential rain and freezing nights. The fortitude and endurance of the Sepik carriers was remarkable. I carried a shotgun while each carrier lugged 40 pounds of rations or tools. Hector was up front, boring on like a homing beagle while I acted as ‘arse end Charlie’. lt was my job to make sure no stragglers ended up in a pot. Not that there were any stragglers or possible deserters. The Sepiks were a long way from home and in hostile territory; consequently they stuck really close. On the eighth day we were at 7000 feet in moss forest when we hit Slate Creek.

We broke out of the dim forest into a clearing, Baden and his team were flat out shovelling and washing the gravel and with the noise of the tumbling water they didn't notice our approach even with a 'cockatoo' billy boy who was stoking the fire. Hector was none too pleased.

‘What the bloody hell are you doing letting someone come up on you like that. That’s how poor old Helmuth Baum went off.'

Baden just laughed and slapped his brother on the back, ‘..you worry too much. Did you bring the rum and smokes, that's the important thing.’

It was almost knock off time so Baden's boys piled their shovels and came over to talk with our new line of workers. They were all Sepik men so they had plenty to talk about. After kai kai, the boys wrapped themselves in army blankets and crawled under the tarpaulins that lined their tent floor. We slept in kangaroo rugs up on a low bamboo table that protected us from the night deluges that coursed through under our tent. The two boss boys took turns at the night watch and kept the fire stoked up.

I noticed that both my cousins slept with shotguns beside them. Baden had his line up early. He sent one team under Kumeri, his boss boy, upstream to work on a rivulet off Slate Creek. He gave Kumeri his Purdy shotgun and gave him his final instructions were:

'Kumeri, yu workim strong. Yu lukim out good bush kanaka callim Kukukuku. Dis pella Kuku all same puk puk. Yu no lookim, yu no hearim. Dis pella i makim yu dai pinis.' With that warning, the 10 workers splashed off upstream with their tools and rations for the day.

We worked on three sluice boxes. On the floor of each box were five coir door mats that collected the heavy gold dust as it coursed through. Each of us was stationed beside a box and fished out any promising quartz for later work. Every hour we washed the mats in a shallow bath to collect the gold dust which would be treated with mercury at the end of the day. Just on lunch, Hector called out, 'Keep working, visitors,' to Baden, reassuring him that they were the regular trade contacts and moved across the creek to conduct the day's trade.

Everyone stopped work to watch the negotiations. There were at least 20 Kukukukus in bark hoods standing motionless among the trees. These were the legendary forest men, feared alike by highlanders and coastal people. Baden picked up his shotgun and motioned the Kukus to stay where they were. He walked towards them as three of them came forward with bilums of sweet potato. They laid them on the ground and stepped back. Baden laid out sticks of tobacco and a small heap of salt on a banana leaf. The Kukus pulled back one bilum of kau kau and said something. The bartering continued with additions and subtractions to find mutual agreement. The other Kukus continually put in their threepence worth and began edging forward for a closer view of the dealings. Hector noticed this and waved his gun at them.

'Back up you mob! Go on! Raus! Raus!’

Hector could sniff their mood. They were now holding their bows in front of them. The Sepik labourers sensed something too and sidled behind their sluice boxes still grasping their long handled shovels.

'Yu pella lookim good. Suppose mi pella shootim, Yu pella get ready pight.’

Baden finished trading and dragged two bilums back. The Kukus carefully slipped the tobacco and salt into their carry purses. There was no move to disengage.

‘Watch this lot Baden, something’s on.’

The scene remained frozen for several minutes, then two shots from upstream. Arrows flew towards us. Baden and Hector fired together. One shot blasted a log next to a forward trader. Another sprayed the bank between two bowmen. Then two more shots up into the trees. No one was hit but the shock did the trick. The Kukus melted into the bush.

'Stay close! nobody move!’

We didn’t have to wait too long. Kumeri’s upstream team almost over-ran the camp as they charged along the stream with the devil on their tails. They huddled up behind our workers. They were no longer men but terrified children. Kumeri was clearly shaken but more coherent than the rest.

‘Masta yu talk true. One pella belong u mi, i die pinis. Mi shootim one pella bush kanaka.’

Two of Kumeri’s team were wounded so Baden got out his medicine box which was an Arnotts biscuit tin. Hector got into gear. ‘George, Kumeri, come with me. Baden, sit tight. Any trouble, fire two shots. Hear any shots, sit tight, we'll get back.’

When we reached the number two box the only movement was a dribble of water out of the sluice. The dead Sepik labourer was lying in the stream with his head bashed in. He’d probably made a dash for it and been picked off. Up on the bank was a dead Kukukuku with a shot right through him. Hector followed a trail of blood up the track. Another Kuku had dragged himself home. Two long handled shovels had blood and hair on them so there must have been some close quarters fighting.

Kumeri rehearsed the story again. He was able to get off two shots that made the Kukus hesitate. The Sepik labourers were able to back off into the quarry face with their shovels. The Kukus moved in for the kill with their stone axes but the Sepiks didn't follow the script. They didn't panic and scatter but used their shovels to good effect.

he instant of ambush had gone and the Kukus melted away in the face of resistance. Hector wasn't fully satisfied.

‘But what were you doing up on the bank away from the others? Peck peck or what?’

Kumeri had no answer to this but just looked blank. We hurried back to the camp where Baden was weaving his medical magic with iodine, silk thread and sewing needle.

ector recruited the dead Sepik's 'one talks' to recover his body. They refused to touch the dead Kuku so I propped him up against a tree for collection. We bagged up the dead Sepik’s head and trussed him onto a pole for carrying. Back at camp, Baden wasted no time in burying him. They dug a hole high up on the bank above flood level.

lways the prospector, Baden commented, 'This looks very promising gravel,' but he didn't persist with it. The deceased's friends paid him the last courtesy of lining the grave with ferns and covering his body with banana leaves before filling him in. The mourners sat around the grave moaning and tugging their hair. Hector called a meeting.

'Watch it. Wounded Kuku dies, so score two to one. Payback then applies.’

I now understood why the brothers had fired so wildly. It didn't pay to inflict too many casualties if you didn't want the payback blood feud to continue. If your side was in front, the fight must go on.

‘Scared the shitter out of them. Might feel lucky again. No more trading. Raus them. George you'll have to go to Wau for rations. Report the dead Sepik there. Ian Mack’s the ADO.’

Hector unwrapped a school exercise book from an oilskin parcel, ‘What's the date?’ There was some argument over that but we settled on 13 April 1933. Baden licked a purple indelible pencil and began printing:

’Slate Creek.-- Upper Watut-.. To ADO Wau from Hector Wales. Report murder of carrier Mailala Maui while shitting in bush--- murderer unknown. Carrier contracted from recruiter Sid Campbell Salamaua. Please inform.’

Baden handed the folded page to me with some further advice.

‘Now don’t mention the attack or shooting. If the Admin. gets a sniff of trouble, they'll close the whole area down.’

Baden was not big on speeches either but while he was at it he was all inclusive.

‘By the way Hector, while you were up the creek I quizzed the boys and they put Kumeri in. It was not peck peck that called him away but push push. A couple of meris were seen across the creek giggling and making sign language. Kumeri took the bait but was on the ball enough to save the day when the fight began.’

Hector told Baden not to make a fuss about Kumeri's indiscretion but to warn him.

'He's your boy Baden so tell him strong. He won't see home again if he hum bugs about. If the Kukus don’t top him, I’ll dong him.’

Hector closed the proceedings by telling the mourners to call it a day and get ready for work.

'Now listen, work these boys hard. No “sorry too much” bit. Business as usual.’

And Hector meant it. The next two days were flat out. Mailalala Maui up on the bank was soon forgotten.

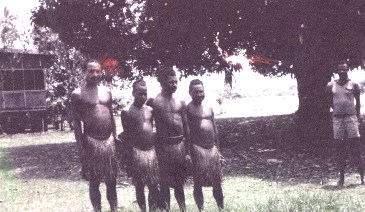

Kukukus in holiday mode, Ihu Sub District Office. (Author's own photo)