The Battle of Bitapaka

The Battle

The loss of submarine AE1 in 1914

|

The task force reached Rabaul on 11 September, finding the port free of German forces. Sydney and the destroyer HMAS Warrego “in the early hours” landed small parties of naval reservists at the settlements of Kabakaul and what they believed to be the German gubernatorial capital Herbertshohe (later Kokopo), on Neu-Pommerm, south-east of Rabaul. These parties were reinforced firstly by sailors from Warrego and later by infantry from Berrima. A small 25-man force of naval reservists was subsequently landed at Kabakaul Bay and proceeded inland to capture the radio station believed to be in operation at Bitapaka, 7 kilometres (4.3 miles) to the south. MacKenzie at Chapter 5 (pp 53 -74) of the official history gives a detailed account of much of this battle. Articles in Una Voce also cover several aspects of the fighting. The advance force of 25 naval reservists was led by Lieutenant Bowen; he was accompanied by Captain Brian Pockley of the Army Medical Corps. Soon after landing a further 10 men reinforced the advance party. With the assistance of a Chinese who ran a small trading store on the Herbertshohe (Kokopo) Road, Bowen lead his party to a narrow road he was told would take him to the Bitapaka wireless station. Instead of staying on the road, which lay like a clear white gap between tall forest, Bowen pushed forward through dense jungle and closely-matted undergrowth that flanked the track on both sides.

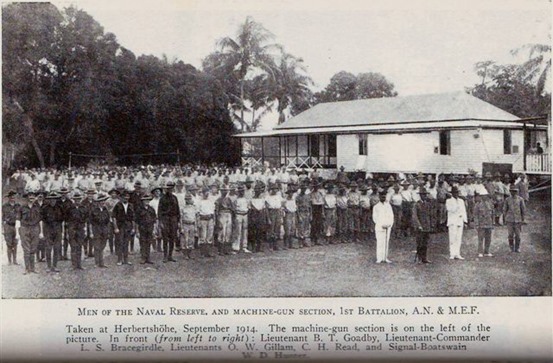

Bowen's avoidance of the open track, partly by accident, allowed two members in advance, Petty Officer Palmer and AB Eastman, to spot a German and about 20 Melanesian soldiers in one group and two more Germans and a Melanesian watching the advance of some of Bowen’s party who had kept to the road at that point. Palmer fired at the first German, probably the first small arms shot by an Australian in the war, wounding the German, alerting also Bowen and his men. The wounded German, deserted almost immediately by his troops, dropped his rifle and before he could deploy his revolver was covered by Palmer and surrendered; thus Sergeant-Major Mauderer of the German Imperial Force became the first Australian prisoner. With a fractured right hand caused by his wound he was taken to Bowen. Bowen coerced Mauderer to walk along the track and call upon the German troops to surrender; as a result, confused, two other German officers were tricked and induced to surrender, one of them Captain Wuchert, the other Lieutenant Mayer. Hence by stroke of luck and use of the German decoy, the commanding officers of the Bitapaka section of the German forces and of the Herbertshohe forces had both fallen into captivity. It deprived the German forces of two senior officers: more important still, detailed maps of the road were found on the prisoners. To Bowen, who was working from a map which gave only a vague outline of the terrain east of Herbertshohe, the additional information thus gained was invaluable. Furthermore the false report, given by Mauderer under coercion, that 800 men were advancing along the Bitapaka road, reached von Klewitz at Toma during the afternoon. Messages conveying the true strength of the landing parties failed to get through, a scared planter having cut the telephone lines from Kabakaul. Mauderer's statement was accepted as correct, and communicated to Haber, with the result that all attempts to maintain the defence of the coastal belt were abandoned, and Haber was confirmed in his intention of moving the seat of administration from Toma farther inland. Captain Pockley shortly afterwards amputated Mauderer’s hand as the only means in the circumstances to save his life. Bowen pressed on with what he now knew would be a contested assault on Bitapaka. He sent the prisoners back to Kabakaul and asked for reinforcements. Anticipating the request, 59 men from the Yarra and the Warrego were landed almost immediately under command of Lieutenant Hill. Later, perhaps early afternoon, No. 3 Company of the Naval Reserve under Lt Gillam, No. 6 Company under Lt Bond, the machine gun section under Captain Harcus, and a detachment of the Army Medical Corps were sent ashore under the command of battalion commander, Commander Beresford. It appears that at least part of these reinforcements were within a mile of Bowen’s position around noon, by which point he had himself been seriously wounded. Pushing forward, Bowen’s main party encountered acute but not always accurate fire from rifle pits and snipers. At about 9.30 am, Able Seaman W G V Williams, who was one of the party left in file along the road to maintain communications back to base, was shot and mortally wounded from a concealed position along the track. Captain Pockley attended upon him and arranged for him to be sent to the rear accompanied by AB Kember to whose hat Pockley attached the red-cross brassard he normally wore on his arm. Soon after, attempting to advance along the road, Pockley (without his red-cross brassard to shield his non-combatant role) was himself shot and mortally wounded. Thus Williams and Pockley died during the afternoon becoming the first and second Australian soldiers to fall in World War I. MacKenzie observed: “Pockley’s action in giving up his red cross badge, and thus protecting another man’s life at the price of his own, was consonant with the best traditions of the Australian army, and afforded a noble foundation for those of the Australian Army Medical Corps in the war.” By around 10 am, Bowen’s force had been joined by the reinforcement from the Yarra under Lt Hill. Engaging a heavily defended trench across the track, Bowen was shot by a sniper from the scrub and seriously wounded. While so engaged, the reinforcements coming from the Berrima also came under fire, losing as they advanced Signalman Moffat and Able Seamen Courtney. Mounting a bayonet charge on the trench, Lt Commander Elwell was shot dead. “But the end came almost immediately after the shot which killed Elwell. With the arrival of the reinforcing company Kempf’s position (in the German trench), had become untenable; his troops were far outnumbered, the trench was outflanked on both sides, and escape was threatened. The natives began to cower at the bottom of the trench and, with few exceptions, could not be induced to look over the parapet to take aim. At about 1.30pm, a white flag went up in the trench.” From that point, the force advance under Lt Hill’s command was not seriously contested apart from an incident when a German prisoner, Sergeant Ritter, who had already surrendered with Kempf, attempted to rouse some remaining Melanesian troops to take action, in the course of which he was shot and killed, as were several of the Melanesian troops, and Able Seaman H W Street. Shortly after, Lt Bond and Captain Travers accepted the surrender of the wireless station by about 7 pm. By the end of the day, Australian casualties were 6 killed: 2 officers (Captain Pockley and Lt-Commander Elwell) and 4 ratings (Able Seaman Williams, Signalman R D Moffatt, Able Seaman J E Walker serving as J Courtney, and Able Seaman Street): 1 officer and 3 men were wounded. Four of their number were buried in the precincts of what is now the Bitapaka War Cemetery, wherein lie also the graves of the much more numerous casualties of WW2. On the German side, the casualties were officially reported as one white NCO and 30 native Soldiers killed and one white NCO and 10 native soldiers wounded. The prisoners taken were 3 officers, 16 white NCOs and men and 56 native troops.

|